Don’t leave, I want to say. But the Heraclitus Snowglobe is already forming.

It’s too late: her seven-year-old self is being petrified. She’ll never be seven again, and there’s nothing we can do. Tomorrow is her birthday, and time is generating a Heraclitus Snowglobe that contains her seven-year-old smiles, tears, tantrums, jokes. It’s not a sad time, but it is the end of an era.

I hold the era in my hands.

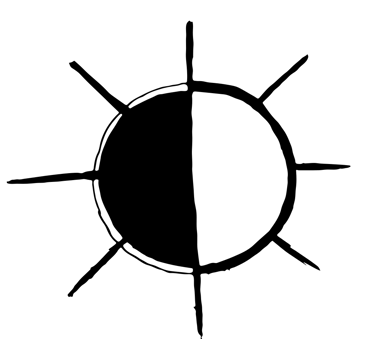

A defined period of time crystallized into what I call a Heraclitus Snowglobe: a continuum of polar-opposite material I can shake. Experiences, I’m thinking, may be collected along a continuum that grows with time—that time determines the size of the experiential spectrum.

The longer the time, the wider the spectrum, and the more extreme the experiences. Time allows polar opposites to stretch away from each other; this gives access to more horrifying, but also more blissful, experiences.

I speculate that a single experience may touch multiple points of the spectrum at once. When my mother died, for example, I experienced the most intense pain and the most intense love simultaneously. Is it possible that this happens with every experience? Maybe. Could it be that experiences come already balanced?

If experiences always contain the same ratio of polar opposites, and time merely allows the spectrum to grow—while the proportion between good and bad remains constant—then perhaps this is why Marcus Aurelius said that a man of forty has seen it all. In that case—and the Stoics would agree—a one-year-old has seen it all too. Two different spectrum sizes. The same ingredients.

As I say goodbye to my seven-year-old, I welcome the older girl into my home. Seven Snowglobes I’ve been lucky to collect. They are all the same, says Marcus.

Good. I look forward to living out the same continuum with this amazing human.